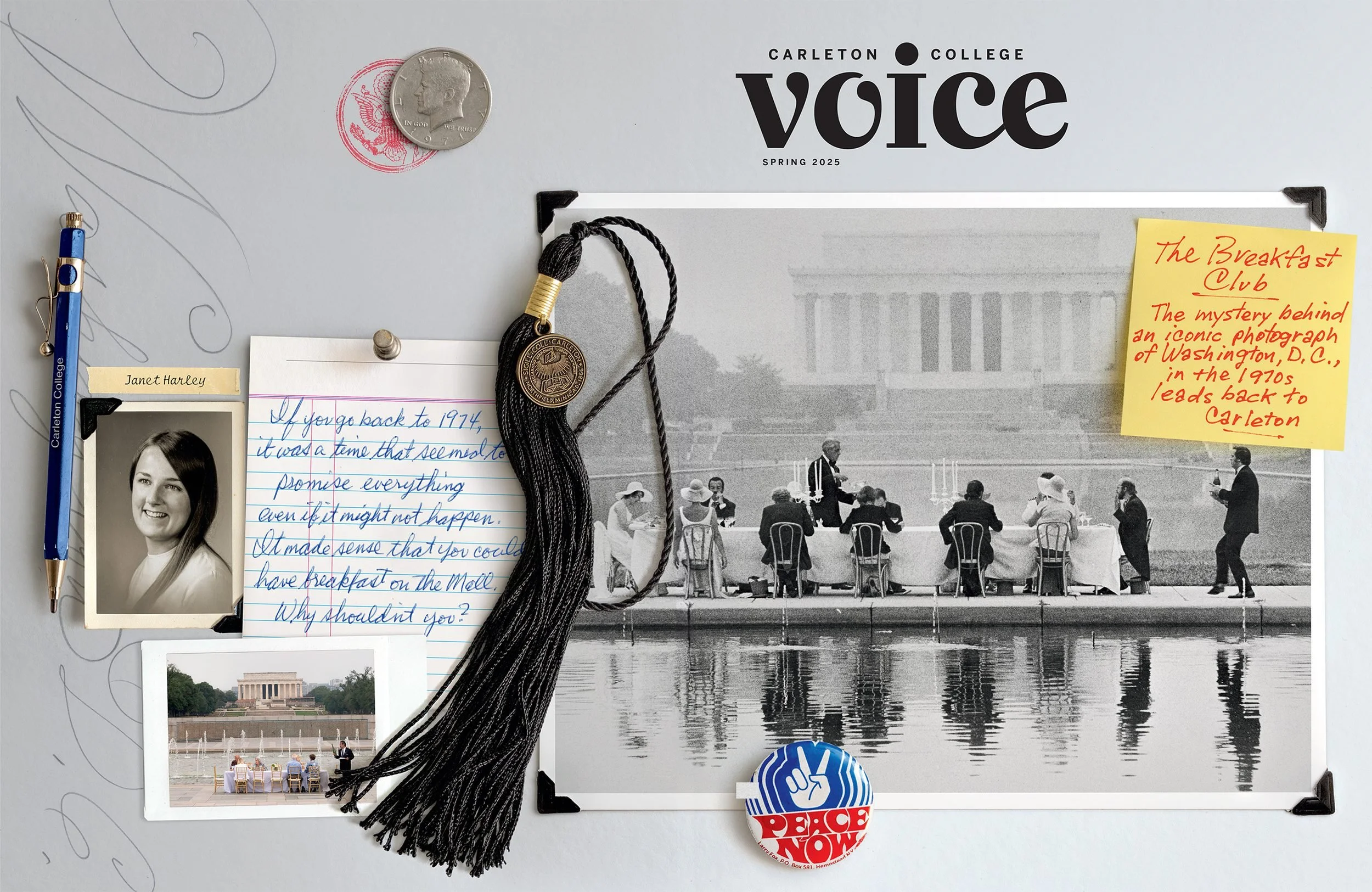

The new issue is one of my favorites, thanks to two incredible anchor pieces. Former Minnesota Monthly editor returns to deliver a powerful story. Long before pop-ups and flash mobs, an unusual sight met visitors to the National Mall on the morning of July 19, 1974: a formal breakfast in view of the Lincoln Memorial, complete with horse-drawn carriage, a string quartet, and candelabra. Captured by a photographer for The Washington Post, the image has since become one of the paper's best-selling prints. Tim Gihring shares the poignant story of recent Carleton College graduates, all drawn to DC to serve their country, pulling off an audacious surprise for a beloved classmate. The piece was animated by artist Jack Molloy, who created tableaux for the front and back covers and story spreads using keepsakes shared by alumni. Another return: multiple James Beard Prize–winning culinary writer heads back to campus to revisit her college cafeteria in a poignant (and hilarious) remembrance. And: Carleton’s Curious Collections, a look at career pivots, and some “real talk about small business.”

Carleton Voice wins a CASE silver award

June marked my second anniversary at Carleton College, and my first time entering the CASE Awards, the global nonprofit association promoting higher ed. I’m pleased to note that the Carleton College Voice took home a silver Circle of Excellence award from the Council for Advancement and Support of Education for our three 2024 issues.

From the judges:

Carleton College Voice was one of our favorites. The design was excellent and the graphic elements stood out. We felt these pieces 'really broke away from the public relations machine' and told stories that were bold, fun, and in some cases truly brave, and even sometimes risky—but oh so important. The writing was sharp, excellent, and often laugh-out-loud funny. A good read rendered beautifully.

Seven higher-ed institutions received awards in the category for colleges and universities publishing three or more times a year, with Holy Cross taking gold, Wake Forest also taking silver, and bronzes going to Boston University, the University of Pittsburgh, Bowdoin, and Kenyon.

Illustration for Kao Kalia Yang’s TRIO story, by Rebecca Sunnu Choi

Fall 2024 Voice: Kao Kalia Yang, Jack El-Hai, Roger Faust

Another issue of the Carleton College Voice is in the can, my fourth as editor. Highlights:

• Kao Kalia Yang, the Minnesota Star Tribune’s artist of the year (2024) and a 2003 Carleton grad, writes about TRIO, the student support program that helped her and other low-income and first-generation students overcome academic, financial, and cultural challenges to fully participate in college life.

• Tim Gihring profiles writer and public historian Jack El-Hai as his 2014 book The Nazi and the Psychiatrist is turned into Nuremberg, a Hollywood blockbuster starting Rami Malek and Russell Crowe. (With photography by Bobby Rogers)

• Bobby Rogers brings his trademark photographic style to a piece on the return of alumni Roger Faust to his alma mater as only the second Indigenous hire; he’ll be teaching land management in the Environmental Studies department.

• With Jaws set to turn 50 in 2025, alumni journalist Liz Ryan looks into research on sharkmania’s odd staying power by UT-Austin professor Janet Davis.

• And more…

A Flag in Flux: The Fall 2024 Issue of the Carleton College Voice

The new issue of the Carleton College Voice opens with a cover image by alumni photographer Amadeo Lasansky, who captures a flag from below. As I write in the intro to the issue's politics section, perhaps this unexpected perspective opens the image to interpretation in ways the iconic billowing version doesn't: "Is it unfurling or curling in on itself? More broadly, do Americans, regardless of race, gender, and political affiliation, see it—and 'the republic for which it stands'—the same way, as a symbol of 'one nation, indivisible, with liberty and justice for all'?” A sobering question in light of today's political realities.

Inside, read perspectives on the historically important November election, from my piece on how journalists from outlets like NPR, Politico, and the Washington Post are covering the election in the face of mounting distrust in the media to Jon Spayde's deep dive into the conspiracies and disinformation that aim to influence the vote. Plus, see how alumni artists Mildred Beltré, Erica Lord, Ethan Murrow, and Christina Seeley reinterpret the traditional get-out-the-vote poster (the posters are perfed in the print issue and downloadable online), each contextualized with writing by my Ostracon partner, art writer Nicole J. Caruth.

From West to East: New rural series launches at the National Gallery of Art

As guest editor of the Midwest region of the just-published National Gallery of Art series “West to East,” I invited three rural writers to share their perspectives on how place shapes creativity—and contributed a writing of my own.

Called Back: On George Morrison, Land Acknowledgement, and Returning Home

Artist Andrea Carlson writes about the art of George Morrison and her return to Gichi Bitobig (Grand Marais), a landscape that influenced Morrison deeply. A member of the Grand Portage Band of Lake Superior Chippewa, she parses what’s left out when we see didactic labels for Morrison’s art that leave out so much of the story.

An aerial view of Francis Xavier Church, the Chippewa City church George Morrison and his family attended. Photo: Jenn Ackerman and Tim Gruber

Modernist Barns and Modern Farmers

Owner of Pied Beauty Farm and associate professor of English at the University of Wisconsin – Whitewater, Joshua Mabie looks at the ways artists like Grant Wood leveraged agrarian symbolism, unwittingly obscuring the reality of life for rural people. Fun fact: while the house in Wood’s American Gothic remains a tourist destination in Iowa, the red barn over the couple’s shoulder never existed: “[It] is a figment of Wood’s imagination, added to confirm the painting’s rural setting.”

Iowa Artists Craft Complex Visions of the Rural

Matthew Fluharty, executive director of Art of the Rural, focuses on Grant Wood’s immersive Corn Room murals as a way to “understand how land, tradition, and personal experience have motivated rural, regional artists,” from Grant Wood to Timothy Wehrle, Laurel Nakadate, and Duane Slick.

For the fourth piece in the series, I contributed my own writing:

Potter Richard Bresnahan Navigates an “Eco-mutual” Future

For my profile, I visited the resident potter at my alma mater, St. John’s University, to hear about how his experience apprenticing with the Nakazato family’s master potters in Kyushu, Japan, in the 1970s influenced his hyperlocal, eco-friendly, and distinctly Minnesotan practice in Collegeville.

Richard Bresnahan in the St. John’s Abbey Arboretum, Collegeville, Minnesota. Photo: Jenn Ackermann and Tim Gruber.

The series is visually unified by the photography of Minneapolis-based studio Ackermann + Gruber, whose imagery grounds each story in the unique sense of place of these four rural environments. After hiring them for a Carleton College shoot and imagery for a Land O’Lakes project on rural vitality, this is my third time working with this husband and wife duo.

For more of my work with the National Gallery, read:

“If Robert Adams Wants His Eco-Conscious Photography to Change Anything, It’s Us,” August 12, 2022

“Doubling Across Time: Three Artists on Racism, Revolution, and Feminism,” October 22, 2022

“Calder’s Mobile Breathes Life into the East Building,” December 21, 2022

The Winter Issue of the Carleton College Voice

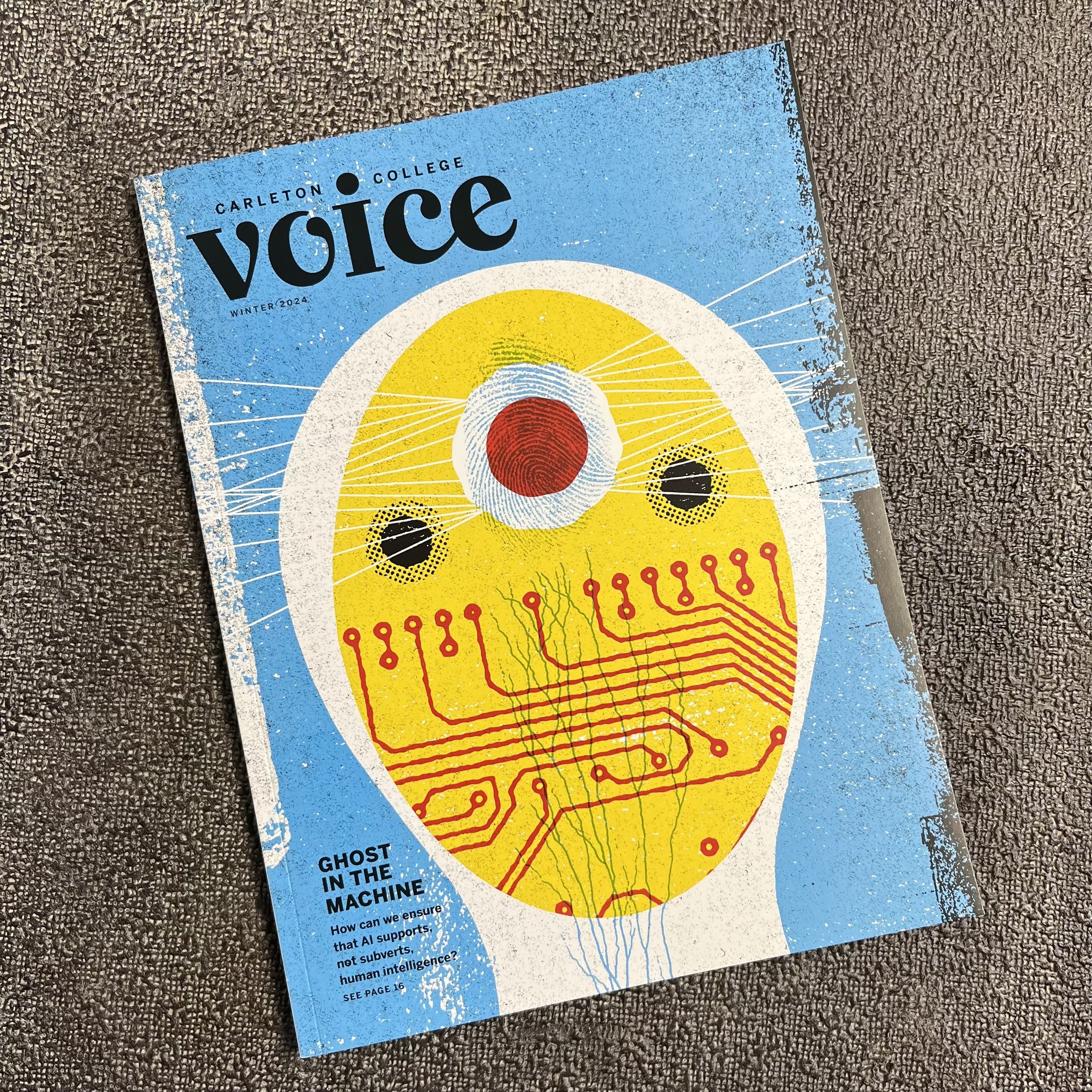

What I love about being a magazine editor is bringing a vision that melds verbal storytelling and visual appeal. And as my first issue overseeing the magazine from start to finish, the winter edition of the Carleton College Voice offers a clear view of both.

For the powerful cover, illustrating Amy Goetzman’s excellent piece on Carleton’s approach to artificial intelligence, I turned to Aesthetic Apparatus’s Michael Byzewski. Art for the cover, inside front cover, table of contents, and the story itself tell part of the story of how the college aims to ensure that AI supports human intelligence instead of subverting it. Byzewski deftly melds a gritty, handmade aesthetic—including some throwback imagery like library cards and anatomical illustrations—with modern symbols (keyboards, binary code, circuitry).

The issue also includes my first feature, a profile of David Lefkowitz, an art professor and artist so varied in his practice that he jokes every solo show he’s in is a group show. He makes oil paintings, minimalist sculptures, conceptual works, public practice. In one series, he envisions Nirthfolde, a “college town situated in a parallel universe that neatly overlaps Northfield” (Carleton’s town) by making tourism-style brochures of local attractions many might overlook. One maps the 89 Sod Wedges of Nirthfolde, those weird patches of grass built into new sidewalk projects. Another maps the 97 trees in the four quadrants of Northfield’s Central Park, renaming them after first names popular in the US during four decades.

“Addressing trees by forenames implies intimacy,” I write. “We name our pets, Lefkowitz points out, yet many farmers refrain from naming livestock destined for the freezer case. ‘What does it mean to give something an identity?” he asks. “Are there ways that we can engage with the world that might resensitize us to the environment?’”

The piece, which quotes Robin Wall Kimmerer, Carleton art historian Ross Elfline, and art professor Jade Hoyer, is illustrated by the family photography duo Ackerman + Gruber, whose superb mastery of light and shadow really brings Lefkowitz’s art to life.

The issue is rounded out by: a feature by former Utne Reader stalwart Jon Spayde, who chronicles how Minnesota legalized adult-use marijuana while keeping both racial equity and economic opportunity front and center; interviews I did with Carleton’s new chaplain (a non-believer) and a pair of 90-year-old alums whose witty banter and recollection of literature inspired me to name my new puppy after Willa Cather; and two pieces on artist and photography professor Xavier Tavera, including the first in our Object Lessons series, which looks at instructional classroom items, in this case, the Polaroid’s apartheid-era ID-2 camera.

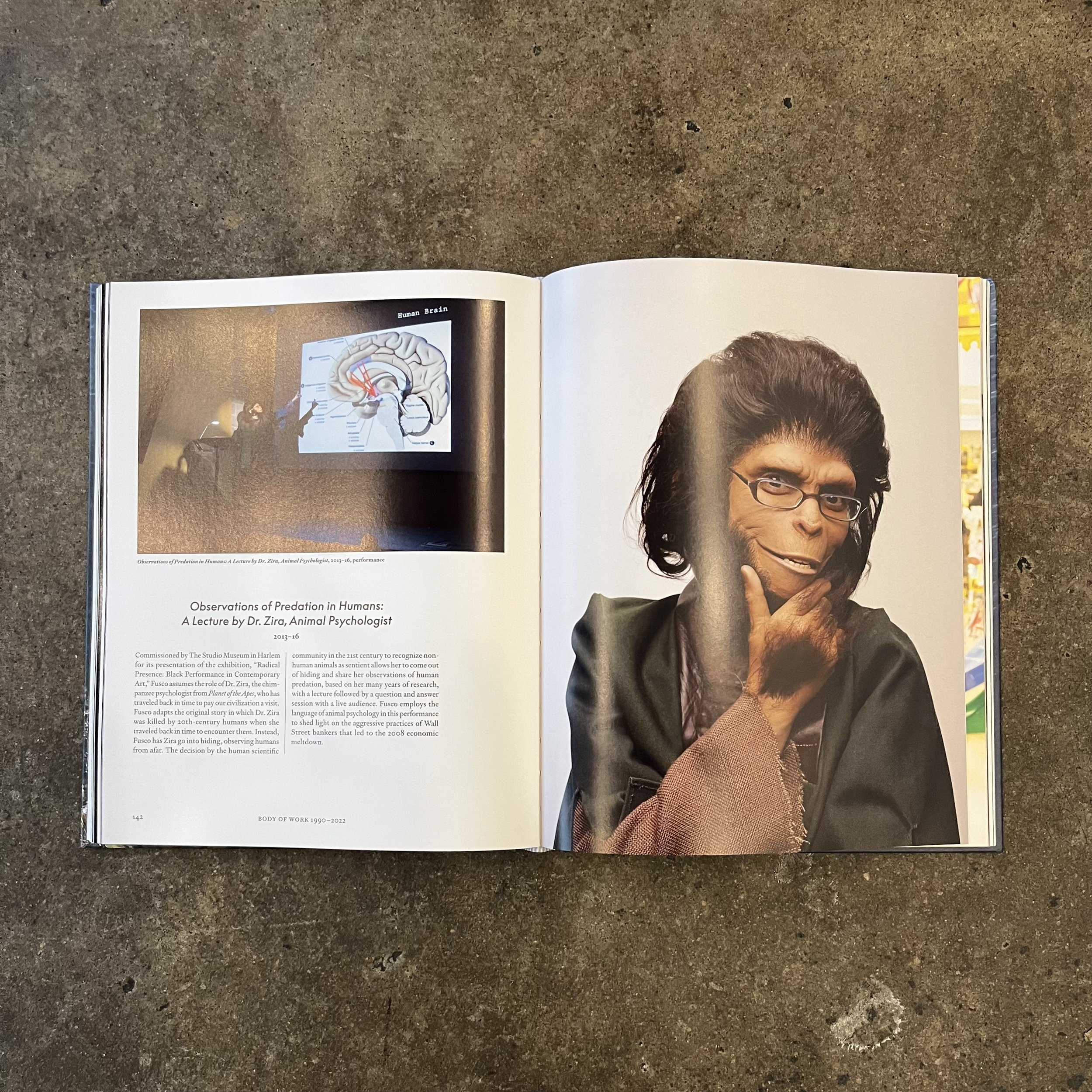

New Coco Fusco Monograph: Tomorrow, I Will Become an Island

I'm excited to receive my copy of Tomorrow, I Will Become an Island, the first career monograph of the great Coco Fusco, after nearly three years of work. Published by Thames & Hudson and edited by Olga Viso, it accompanies an exhibition on view through January 7, 2024, at KW Institute for Contemporary Art in Berlin. I'm incredibly grateful to Olga for inviting me to be part of it: I served as production editor, a role that meant initial edits of all texts (including essays by Jill Lane, Julia Bryan-Wilson, Antonio José Ponte, and others); running logistics between gallery, artist, and publisher; recommending designer Mark el-Khatib; and reviewing all proofs. It's an important and timely volume, and I learned so much, about Coco and book publishing, along the way. Get a copy if you can!

It’s my third professional engagement with Coco: I edited her 2016 Walker Reader essay, “Taste as a Political Matter,” on her first encounter with (and the lasting impact of) the Guerrilla Girls, and in 2015, I interviewed her in the Walker Art Center green room as a special effects artist transformed her into the chimpanzee psychologist from Planet of the Apes before her lecture-demonstration Observations of Predation in Humans, A Lecture by Dr. Zira, Animal Psychologist. Along the way, I got a photo (by Gene Pittman) with the good doctor, along with then curator Misa Jeffereis.

Update 12/14/23: Both Hyperallergic and the New York Times have included Fusco’s monograph among the year’s best art books. In the Times, Holland Cotter writes that this “visually captivating book documents the politics and the poetry, both sharp, of an important career very much in progress.”

My first issue as editor of the Carleton College Voice

After 15 years focusing almost exclusively on digital publishing projects, I'm back in the print world: my first issue as editor of the Carleton College Voice is out. Designed by Nancy Eato, it includes a cover story by Olivia Fantini on Hmong author and librettist Kao Kalia Yang (with commissioned photography by the amazing Pao Houa Her), Sara Harrison's piece asking how prepared we are for the next pandemic (with commissioned art by Piotr Szyhalski/Labor Camp), Andrew Faught's profile of Oppenheimer biographer Kai Bird, an 8-page rollout on overcrowding in our national parks by Laura Theobald, my first editor’s note, and more (including... beavers). Get your hands on a copy if you can, or read it online at carleton.edu/voice.

New for Land O' Lakes: Cooperatives and Care

When weavers were seeing opportunities dry up due to industrialization, when World War II left millions hungry in Europe, when electrification efforts left farmers out, when racism left Black Americans with few decent jobs, and when the COVID-19 pandemic struck: co-ops were there. In a new piece for the 101-year-old agricultural co-op Land ‘O Lakes, I looked at the variety of cooperative business models, from the $30-million Isthmus Engineering & Manufacturing to The Hub bike shop, to see how co-ops thrive in times of turmoil and what promise this model has going forward.

The Hub, my neighborhood worker-owned co-op, is located two doors down from the police precinct at the center of the uprising following George Floyd’s murder. It’s called that block home for more than 20 years, and as the neighborhood continues to rebuild, it’s something of a community anchor, thanks in large part to its cooperative mission. Despite damage to its building and having witnessed neighboring businesses burn to the ground (including Gandhi Mahal, the restaurant at the center of another piece I recently wrote), it’s committed to the neighborhood.

“We’re not going anywhere,” bike mechanic and Hub co-owner Henry Slocum told me. “The worker-owned co-op is not a get-rich-quick scheme, but it has demonstrated that it has the power to build roots and stability and economic vitality in communities. That’s what we’re here for.”

Read “The power of building community roots: What cooperatives can teach us in times of turmoil.”

And here’s part two (although currently misattributed to a different writer), “Creating Cooperative Change: Building a better future starts with working cooperatively.”

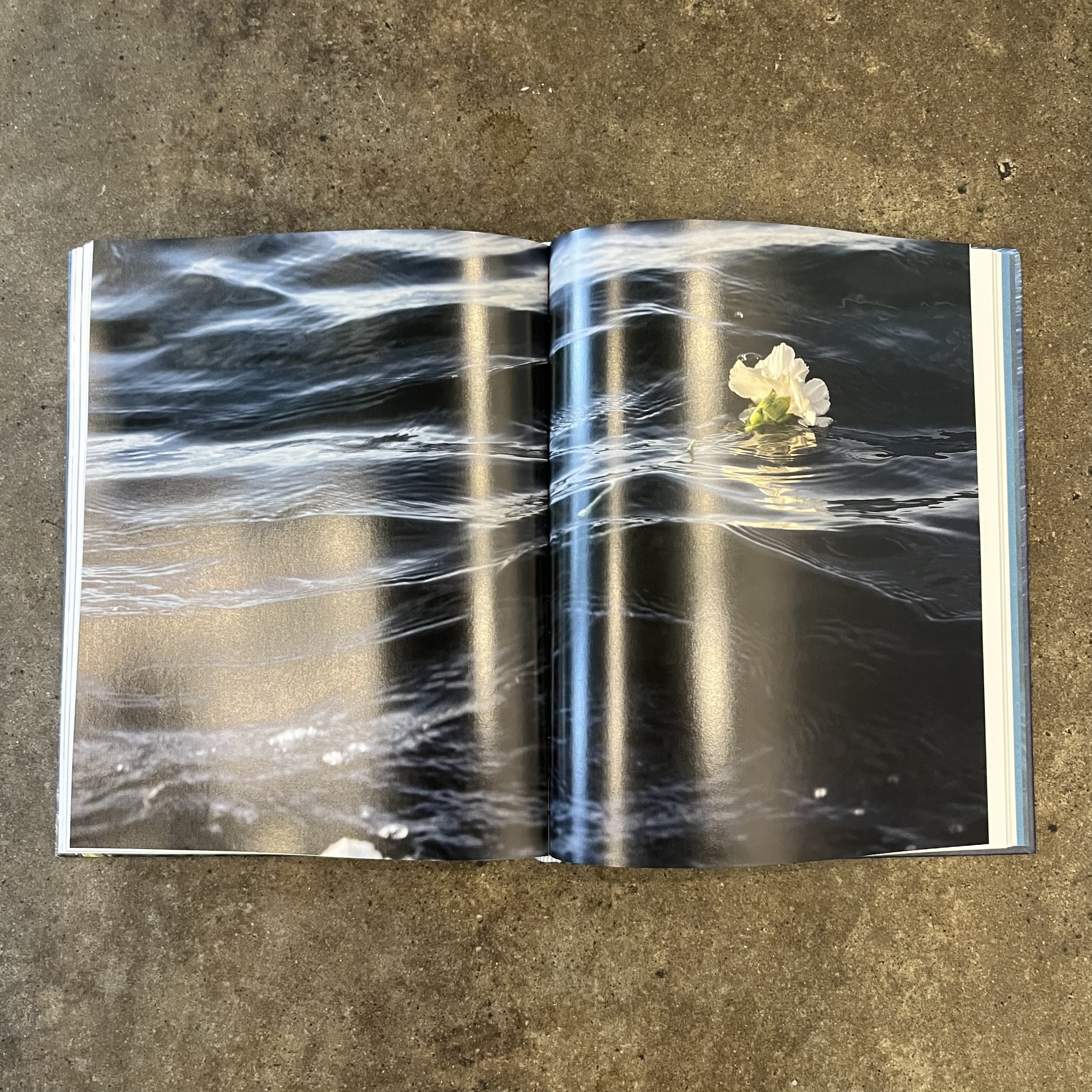

Pao Houa Her, untitled (opium flower with pink fabric), 2022

Pao Houa Her named a 2023 Guggenheim Fellow

Today the John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation announced that Pao Houa Her is among the 171 artists, scientists, writers, and scholars in the 2023 class of Guggenheim Fellows. Based on “prior achievement and exceptional promise,” winners have “followed their calling to enhance all of our lives, to provide greater human knowledge and deeper understanding,” said Edward Hirsch, the foundation’s president. Based in the Twin Cities suburb of Blaine, Pao’s work is deeply conceptual, often investigating the theme of desire for a real or imagined homeland for Hmong people—and it resonates deeply with audiences and curators alike: her work has been featured at esteemed venues like the Whitney Biennial and the Walker Art Center, and she was named artist of the year by the Minneapolis Star Tribune. She’s so deserving of this recognition by the Guggenheim.

One vein in my work that gives me the most satisfaction these days is helping artists tell their stories in clear, honest, and compelling ways. Over the years, I’ve helped artists with editing and grantwriting, with two, including Pao, winning Guggenheim fellowships. (I also co-wrote, with Nicole Caruth, the grant that won us the 2019 Arts Writers Grant from the Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts). If you’re an artist in need of help with language—for artist statements, website text, exhibition descriptions, or grants—please get in touch.

Congratulations Pao!

Hammer Projects: Eric-Paul Riege, installation view, Hammer Museum, Los Angeles, November 13, 2022–February 19, 2023. Photo: Jeff McLane

New Interview: Eric-Paul Riege on Animate Objects, Performance, and Diné Weaving

“I consider everything I do a weaving,” says Diné artist Eric-Paul Riege. “Talking to you, I consider myself the weft and you the warp, and as we’re talking the threads of our lives, our histories, and our futures become intertwined and braided and tangled.” A fiber artist born and based in Gallup (Na’nízhoozhí), Riege makes sculptural installations from natural and synthetic materials—cat fur, sheeps wool, stuffed animals—to examine both his own personal cosmology and that of his Diné heritage. Following solo shows at the Hammer Museum in LA and ICA Miami, Riege recently returned to Minneapolis’s Bockley Gallery, site of a 2021 solo show, for the group exhibition Now You See It, Now You Don’t, on view through April 29. To mark the occasion, we shared our 2021 conversation—on topics including queerness, art activated through performance, and his belief that objects are animate—on Bockley’s newly redesigned website.

Read “I Am the Weft, You Art the Warp,” my interview with Eric-Paul Riege.

Eric-Paul Riege, dah ‘iistl’o ́ [loomz], weaving dance (fig.1) (2018), Sanitary Tortilla Factory, Albuquerque, NM.

Photo by Rapheal Begay, courtesy of the artist

New on the NGA Blog: Calder's Largest and Last Mobile Returns

Read my latest for the National Gallery of Art, “Calder’s Mobile Breathes Life into the East Building,” on the return of newly conserved Untitled, Alexander Calder’s largest and final mobile, to the gallery’s East Building atrium.

Telling Land O' Lakes's "Rooted in Tomorrow" Story

Land O’ Lakes—a 101-year-old, 3,100-member cooperative—believes farmers play a pivotal role in helping solve key issues facing humanity, from food insecurity to rural “brain drain” to climate change. To tell stories of rural American solutions, I worked with Zeus Jones on a pilot editorial project, inspired in part by the audacity of Google X and the editorial excellence of Patagonia Stories. We set out to create six pieces that illustrate the three pillars of Land O’ Lakes’s “Rooted in Tomorrow” mission: stories that illustrate the coop’s values, transcend marketing initiatives and, hopefully, benefit the planet. We wanted stories that are bold, true, altruistic, and emotional—whether they involve Land O’ Lakes farmers or not.

These three values—sustainable futures, vibrant rural communities, and a safe and plentiful food supply—offered a bounty of story possibilities. We concepted dozens of approaches before narrowing to our final six. I interviewed a dozen or so subjects, from rural policy experts and economic development advocates to an education thought leader in Appalachia and a Black farmer in rural Mississippi, to write three pieces. The first two dug into the question of rural values: that is, while values are values, what’s special about rural places that offer rich terrain for exploration, invention, and change? And, more importantly, what can it mean to fully activate those values?

Launching the series was my piece, “In rural America, what you do matters,” which centers Benya Kraus, a Thai/American woman who brought her Ivy League credentials home to her family’s farm community of Waseca, Minnesota, to become a leader in rural economic development.

The second, “Thriving in 'The Middle of Somewhere,'" heads to Aberdeen, South Dakota, to see how connection—human and technological—can contribute to thriving rural communities.

And the third piece, forthcoming, looks at the spectrum of cooperative businesses that Land O’ Lakes is part of and how such a business model—embraced by organizations from the employee-owned Hub Bike Shop in Minneapolis to the hybrid Weaver Street Coop chain in North Carolina to the Wisconsin worker-owned Isthmus Manufacturing and Technology—can be a lifeline for neighborhoods and communities.

Working with the ZJ team, I concepted the remaining pieces, which were written by other writers and tackle issues including the role of rural places in climate resilience, farmers and food security, and the link between rural connectivity and health. I’ll post links here as these final stories are published.

Felix Gmelin, Color Test (Red Flag #2), 2002

New on the NGA Blog: Three Artists on Racism, Revolution, and Feminism

With today’s closing of the National Gallery of Art exhibition The Double: Identity and Difference in Art Since 1900 I belatedly share my contribution to the show, a look at three examples of “temporal doubling”—by artists Christina Fernandez, Felix Gmelin, and Mary Kelly. What do their works, created in 1999, 2002, and 2005, have to tell us about the strange days we’re living in now?

Fernandez melds her own self portraits into works by iconic Mexican photographers as a meditation on racism against Indigenous people. Gmelin’s two-channel video pairs a revolutionary relay race in Berlin in 1968 with a reenactment, using his own students, in Stockholm. And Kelly’s projection morphs between a photo of women at a 1970 women’s liberation march (marking the 50th anniversary of passage of the 19th Amendment) and her restaging of it in 2005. What echoes do their works have today?

Read “Doubling Across Time: Three Artists on Racism, Revolution, and Feminism” at the NGA blog.

Interview: Dyani White Hawk on her Whitney Biennial Artwork

With Wopila | Lineage (2022)—her 14-by-8-foot contribution to the 2022 Whitney Biennial—Dyani White Hawk wanted to make a statement: “I wanted to position Lakota aesthetics in the Whitney Biennial. Native people have not been able to walk into public spaces and see our lives validated, reflected, honored, and uplifted in the way that other folks have. So they’re the first audience I want to address.”

Beyond that, though, she wanted to use beauty—through the meticulous application of more than a half million shimmering glass beads—to open up a conversation with visitors. “‘Wopila’ expresses deep gratitude,” she tells me in a just-published interview.” And "‘Lineage,’ like much of my work recently, is meant to honor and show gratitude for the lineage of Lakota women and their contributions to abstraction, for Indigenous women at large and their contributions to art on this continent, for the generations of practiced abstraction that helped nurture and guide the work of the Western artists that were inspired by their work and brought that back into their studios with them as they created easel paintings. In these pieces I’m pulling from those histories—from my own very specific history of Lakota abstraction, from Indigenous abstract practices at large, from abstract easel painting practices—and hoping to create opportunities for conversation around how connected those histories are and the fact that one doesn’t happen without the other.”

She acknowledges there’s a critique embedded in the work:

It’s recognizing the bullshit that it has been, and the way that it’s been taught so far is extremely racist and sexist and ageist. Without a doubt, it’s a critique of how it has been presented to us and taught to us so far. But I don’t want to just sit in a place of anger. I want to sit in a place of: this is the BS that has existed; now how do we move towards a healthier future?

Read “Beauty Is Medicinal: Dyani White Hawk on her Whitney Biennial Artwork”

Interview: Pao Houa Her on Homelands Lost, Imagined, Constructed

Pao Houa Her was sixteen years old when she saw someone who looked like her on an art museum wall for the first time. Born in Laos and having arrived in the US as a refugee at age three, she was viewing photographer Wing Young Huie’s 1998 Walker Art Center show, which depicted, among others, Hmong residents of St. Paul’s Frogtown neighborhood. The exhibition was an inspiration for Her to take up photography, a move that led her to study at the Minneapolis College of Art and Design, where she earned her BFA, and at Yale, where she was the first Hmong graduate of the school’s photography MFA program. This year marks a momentous return to the Walker for the Twin Cities–based artist: it’s the site of her first solo museum show, Paj qaum ntuj / Flowers of the Sky—an honor that follows her appearance in the 2022 Whitney Biennial (where 54 of her photos were featured) and her third-place prize in the 2022 Outwin Boochever Portrait Competition at the National Portrait Gallery, where her photo is currently on view.

To inaugurate the newly redesigned website for Bockley Gallery (more on that soon), I interviewed Her about her practice and the thread of desire that weaves through all of her work—from the longing for a Hmong homeland for community elders displaced by the war in Vietnam to the search for official recognition by Hmong soldiers who were guerrilla fighters for the US but continue to be denied veterans benefits today.

Her works can be deceptive. Often shot in a traditional Hmong portraiture style, her photos also tell deeper, more complex stories. The portraits of Hmong women in the After the Fall of the Hmong Teb Chaw series, for instance, honor Hmong elders, but also nod to a scandal in the community: these women were victims of a Hmong swindler who promised them a stake in a fictitious Hmong homeland (or teb chaw) in Laos. Shot at a St. Paul senior center and the Como Conservatory, the imagery appears to be set in the lush jungles of Laos, but the reality of their displacement is betrayed by subtle details (a visible cord or electrical outlet, a mix of real and artificial plants).

Pao Houa Her, untitled (portrait), 2017

After the Fall of Hmong Teb Chaw series

The Attention series (2012–2014), too, carries a deeper meaning. Mimicking the aesthetic of traditional military portraiture, the series showcases Hmong soldiers, in dress uniforms, chests laden with medals, and often appearing against a backdrop of red velvet. But while she’s honoring these men on the walls of museums, she’s unable to name them, due to the Stolen Valor Act, which prohibits impersonating military personnel.

She tells me:

With these men, the uniforms and the medals that they wear are not US sanctioned. They’re not provided for them by the United States Army. They’re going out and buying their own uniforms, their own medals, their own pins, and they’re giving it to themselves. There’s that aspect.

Then one has to wonder: if they were in the US military, would they be getting all that? Maybe they would; I don’t know. Then the other aspect: I get that the United States Army has completely forgotten about them and that it’s important to them to be seen. And, as a person who’s making these photographs of them, maybe it’s important for me to name them. Maybe I am contributing to that continued erasure, but also I feel like: why is it up to another Hmong person—why is it up to me to do that, to give them names, when it should be the job of the people who are erasing them?

Please read, “Homelands Lost, Constructed, Reimagined: An Interview with Pao Houa Her”

Robert Adams, The River’s Edge, 2015

New Essay: If Robert Adams Wants His Eco-Conscious Photography to Change Anything, It’s Us

"[T]hough poems and pictures cannot by themselves save anyone—only people who care for each other face to face have the chance to do that—they can strengthen our resolve to agree to life.” That's Robert Adams, whose career retrospective, American Silence, is on view now at the National Gallery of Art, writing in 2005. For the show, I wrote an essay looking at the artist's body of environmental work and how, despite his own leanings as an advocate for sensible policies around logging and climate change, he eschews the label of "activist art," instead offering us something more poetic and personal.

This is the first of a three-part engagement with NGA, so stay tuned for what’s next.

Announcing the 2022 Rabkin Prize Winners

Between stints as an art writer/editor at the Walker Art Center, I was editor at the Minnesota Independent and also the site’s media critic. I spent four or five years documenting media consolidation, newsrooms contracting, and arts and culture writers falling to budget cuts at legacy dailies and altweeklies alike (culture writers were almost always the first let go). Shortly after returning to the Walker to launch its online publishing portal in 2011, I organized an international conference, Superscript: Arts Journalism and Criticism in a Digital Age, as a way to ponder art journalism’s “possible futures” in this climate.

The future was, and continues to be, pretty grim.

So when I was asked to be on the jury for the Rabkin Foundation’s annual prize for arts writers, of course I was thrilled. Help pick eight arts writers to each get $50,000… just for being great, smart, community-connected writers? I’m in.

Over the past six years, the foundation—named after artist Leo and his wife Dorothea Rabkin—has given $2,775,000 to arts writers all across the US. Astounding, really.

For the 2022 Rabkin Prize, I was part of a small but sharp jury—with Sasha Anawalt, founding director of the USC Getty Arts Journalism Program, and Wall Street Journal arts editor Eric Gibson—that deliberated on the work of 16 writers, all nominated by peers who consider them the “essential visual art journalist[s] working in [their] part of the country.” I’m truly excited to help the foundation support these thinkers:

Shana Nys Dambrot

Los Angeles)

LA Weekly arts editor

Bryn Evans

Decatur, Georgia

Poet, frequent contributor to Burnaway

Joe Fyfe

New York City

Painter, writer

Peter L’Official

Harlem & Annandale-on-Hudson, NY

Poet, educator

Stacy Pratt

Tulsa

Writer, musician, poet

Darryl F. Ratcliff, II

Dallas

Artist, poet, arts writer

Jeanne Claire van Ryzin

Austin

Sightlines editor

Margo Vansynghel

Seattle

Crosscut arts reporter

Congratulations to all! And thanks to Rabkin executive director Susan Larsen for including me, and to fellow jurors, Eric and Sasha!

Naming GroundBreak: Transforming the Epicenter of Racial Reckoning to the Epicenter of Racial Opportunity

The murder of George Floyd sent millions into the streets to protest police brutality against Black people and call for equity and opportunity. The uprising responding to such injustice coincided with damage that leveled commercial and cultural corridors across the Twin Cities, prompting a move to rebuild: physically and spiritually—not to mention equitably.

But how? I was invited to be a small part of an ambitious initiative being spearheaded by the McKnight Foundation that aimed to corral resources—and will—to invest $2 billion over 10 years to help rebuild neighborhoods impacted by this destruction and, more importantly, create opportunities for BIPOC community members—and do so while addressing climate change. A group of more than 25 corporate, civic, and philanthropic leaders joined forces, emboldened by a mission: “We have a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to define a new paradigm for community development finance that finally addresses systemic racism; rights historical wrongs; closes racial gaps in income and wealth; and boldly meets the climate moment.”

Its goals:

• Create 45,000 new BIPOC homeowners

• Stabilize families in 23,500 affordable rental units

• Complete 30 commuity-led, climate-ready, transformational commercial developments

• Launch more than 11,000 BIPOC-owned businesses with at least 20 percent employing 5+ people

I was the writer on a team at Zeus Jones charged with naming this vitally important endeavor. It was an urgent project—three weeks start to finish—so we quickly zeroed in on a range of rich territories to explore, from the audacity of the initiative’s scope to the geographic specificity of this moment: this movement started here in Minneapolis, at 38th and Chicago. The name I came up with was suggestive of building, of the anchoring earth, of a break from old paradigms, of a new day rising.

On May 12, 2022, the initiative was christened: The GroundBreak Coalition. Its ambitious goal: “to transform the epicenter of racial reckoning into the epicenter for racial opportunity.”

Insights 2022: Piotr Szyhalski on his Labor Camp's COVID-19 Reports

Artist and educator Piotr Szyhalski took the stage on March 1 to launch the return of Insights, an annual design lecture series put on by AIGA Minnesota and the Walker Art Center. Fitting his theme—his artistic practice and his yearlong COVID-19 Reports project—he spoke from the Walker’s empty cinema to online-only audiences. He began, as his daily drawing project did, listing off current statistics related to COVID: those killed by the pandemic since it began, those killed the previous day, etc. “So this is the context for today,” he said, and then, choking up, there in that empty auditorium, he looked at another dark context: the brutal war in Ukraine. “I am really feeling the weight of history today,” he said, putting the Ukrainian flag on the screen (as far as I can tell, his words mark the first public acknowledgement of the war by this contemporary art center). An artist with rare heart, vision, and technical skill, he went on to dig into that history, from how his upbringing in Poland helped shape his aesthetic and views on free speech, propaganda, and politics to the newer histories, years and months and days old, of corruption and disinformation around this deadly pandemic. Piotr was kind enough to mention my April 2020 article on his COVID project, “NO HOLDS BARRED! A Look at Piotr Szyhalski's Daily COVID-19 Reports,” which at the time—only a month into the project—helped him think about the series as a continuous project instead of just a series of daily reflections (you can watch it here).

And to quote Piotr, “Slava Ukraini!”